Sponsored Books

- Garden At Monceau

- Briefe eines Verstorbenen (Letters of a Dead Man)

- Andeutungen über Landschaftsgärtnerei (Hints on Landscape Gardening)

- City of the Soul: Rome and the Romantics

- Romantic Gardens: Nature, Art, and Landscape Design

- Writing the Garden: A Literary Conversation Across Two Centuries

- Learning Las Vegas: Portrait of a Northern New Mexican Place

Recommended Books

- Henry David Thoreau: A Life by Laura Dassow Walls

- A Political Imperative

- Afton Villa Book

- Celebration of the publication of A Natural History of English Gardening 1650-1800 by Mark Laird

Book Reviews

- Spying on the South: An Odyssey Across the American Divide

- American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic

- National Park Roads: A Legacy in the American Landscape

- Pückler Letters

- Top Ten Garden Books of 2013: Writing the Garden

- Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer

Articles

Pückler Letters

As a follow-up to Pückler’s Andeutungen über Landschaftsgärtnerei (Hints on Landscape Gardening), which the Foundation for Landscape Studies published in association with Birkhäuser in 2014, we are continuing to resurrect the reputation of one of the most important figures in landscape-design history.

As a follow-up to Pückler’s Andeutungen über Landschaftsgärtnerei (Hints on Landscape Gardening), which the Foundation for Landscape Studies published in association with Birkhäuser in 2014, we are continuing to resurrect the reputation of one of the most important figures in landscape-design history.

Written during the years 1826 to 1828, Letters of a Dead Man ranks along with the novels of Charles Dickens as a work of delightful and frank social criticism and a penetrating portrait of English customs and English scenery in the first third of the nineteenth century. The trip that Pückler recounts in such a lively fashion was taken in the hope of finding a British heiress who would be able to finance the continued conversion of two thousand acres of his vast realm near the southwest corner of Silesia into a Romantic landscape.

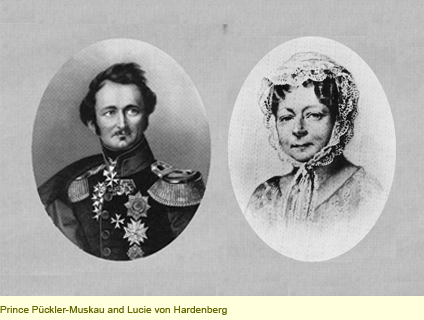

In order to facilitate the prince’s bride quest, he and his wife of nine years had gotten a divorce. But this hardly meant that their union was dissolved. The idea was for Lucie (referred to in the Letters as Julie after the protagonist in Rousseau's novel Julie, or the New Heloise) to remain at Muskau and oversee the continued creation of the park while the two stayed in touch through a regular exchange of letters in which Pückler kept her apprised of his adventures abroad and she kept him up to date about happenings at home.

To give the flavor of the prince’s personality, literary flair, and observant eye, here are some excerpts from one of the letters in this magisterial compendium of Pückler’s correspondence.

Cheltenham, July 12, 1828

My Precious Julie,

I left London at two in the morning, this time really sick and in a very foul mood, in harmony with the weather, which, utterly à l’anglaise, was raging like a storm at sea, the rain pouring down in buckets. But after the sky cleared up around eight o’clock and the gentle, swift roll of the carriage allowed me to slumber a little, I found everything refreshed and sparkling like emeralds, while through the open carriage window a magnificent fragrance wafted in from the flowery meadows. And then, within a few moments, your morose friend, so burdened by worry, became an innocent child once again, taking delight in God and the beauty of the world. . . .

Our road passed through a part of the countryside that was bursting with luxuriant vegetation like the loveliest park. Next we were presented with fields of grain as far as the eye could see, and without hedges—a rarity in England. . . .

Late in the evening I arrived in Cheltenham, an enchanting spa town of an elegance not found on the Continent. My mood was already cheerful and comfortable because of the copious gas lighting and new-looking, villa-like houses, each surrounded by a little flower garden. This is always my favorite time of arrival, when the daylight is in competition with artificial illumination. I entered the inn, which could almost be called sumptuous, and went to my room preceded by two servants who lit my way, first up a snow-white staircase of stone adorned by a balustrade of gilded bronze, and then across bright gleaming carpets. . . .

It would be the sweetest pleasure to travel here with you, free of cares and duties. How much I miss you everywhere. And I must love you deeply, my dear, because whenever things go badly for me, I am always comforted by the thought that you at least escaped that moment; and on the other hand, whenever I see or feel something that makes me happy, I must always—as if it were a reproach—experience a pang of regret for enjoying it all without you!

As it turned out, Pückler’s pursuit of an heiress proved fruitless, and he and Lucie never became a wealthy ménage à trois. Nevertheless, the sales of Briefe eines Verstorbenen, with an endorsement by none other than Goethe, launched Pückler on a career as a travel writer. Chronicling his journeys to foreign parts, including Algeria, Tunisia, Sudan, Asia Minor, and Greece, he was able to keep his principality financially solvent, at least for a time, as he and Julie continued their great park-making enterprise.

As it turned out, Pückler’s pursuit of an heiress proved fruitless, and he and Lucie never became a wealthy ménage à trois. Nevertheless, the sales of Briefe eines Verstorbenen, with an endorsement by none other than Goethe, launched Pückler on a career as a travel writer. Chronicling his journeys to foreign parts, including Algeria, Tunisia, Sudan, Asia Minor, and Greece, he was able to keep his principality financially solvent, at least for a time, as he and Julie continued their great park-making enterprise.

All you have to do to become acquainted with this charming personality and animated and witty writer is to click here.