Place Travels

- The Healing Angel of Central Park

- A Rush to Drill, Because We Can

- Discover garden paradises, granite boulders, and moss-carpeted forests.

- New York Environs

- Romantic Rome

- Villa Lante

- Vaux-le-Vicomte

- Two Cities, Two Parks: Saturday in Paris, Sunday in New York

- Traveling Through the Netherlands and Belgium

Traveling Through the Netherlands and Belgium

“I hope it doesn’t rain while we are traveling in my country,” said Dutch landscape historian Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, as we reviewed the itinerary for the Foundation for Landscape Studies’ May 2013 tour of the Netherlands and Belgium. But rain it did, practically every day of the trip. Surprisingly, however, as we went around the table recounting impressions and experiences at our farewell dinner, almost everyone mentioned that the rain had actually enhanced their impressions of the historic and contemporary gardens we had visited. Thanks to the unseasonably cool weather, tulips and pear trees were in bloom at the same time as majestic chestnuts that normally flower later in the spring. The intermittent rain gave a gleam to grass, tree leaves, and verdant moss carpeting a former hunting preserve of an old estate, while the wet ground and decaying leaves on woodland paths released an earthy fragrance. Virtually everyone seemed to agree that the atmospheric mistiness had given the gardens and parks we visited a special quality.

There was another aspect of Dutch wateriness that we came to appreciate – the astonishing fact that more than 20 percent of the country lies below sea level. Amsterdam is built twelve feet below the ground’s normal surface, and its famous canals are a historic reminder of the unremitting determination on the part of the Dutch to create new land where there was none before.

The coastal provinces of the Netherlands are home to 21 percent of the nation’s population of 16.5 million. Since some members of our group were particularly interested in the problems of worldwide climate change and sea-level rise, we met two days in advance of the tour with water management experts who described new and traditional techniques for Dutch land reclamation, drainage, and coastal defense.

Water Management. Our first day was spent driving through Noord-Holland with Dr. Jaap Evert Abrahamse, a landscape historian, who explained how its ubiquitous polders were created in the early seventeenth century by constructing a strong system of dikes around the Beemster and Schermer lakes. The dikes were rimmed with a surrounding canal, into which an array of wooden windmills pumped water from the lakes. Surveyors proceeded to draw up a mathematical plat of the newly exposed land. Beside the resulting checkerboard of large squares subdivided into smaller squares and further parceled into uniform, long, rectangular fields, numerous wooden mills still perform their historic function as pumps. A visit to the De Cruquius Museum, containing a nineteenth-century, steam-powered pumping station, showed how nineteenth-century Dutch engineers were able to take advantage of new industrial technology. Now electric power is the main source of energy for lifting groundwater over the edge of a dike into one of the many drainage canals that carry it away. Added background information on Holland’s polder history was provided by Jandirk Hoekstra, of H+N+S Landscape Architects, during lunch on top of the Hondsbossche Zeewering, a huge barrier protecting the low-lying polder lands from the North Sea.

Water Management. Our first day was spent driving through Noord-Holland with Dr. Jaap Evert Abrahamse, a landscape historian, who explained how its ubiquitous polders were created in the early seventeenth century by constructing a strong system of dikes around the Beemster and Schermer lakes. The dikes were rimmed with a surrounding canal, into which an array of wooden windmills pumped water from the lakes. Surveyors proceeded to draw up a mathematical plat of the newly exposed land. Beside the resulting checkerboard of large squares subdivided into smaller squares and further parceled into uniform, long, rectangular fields, numerous wooden mills still perform their historic function as pumps. A visit to the De Cruquius Museum, containing a nineteenth-century, steam-powered pumping station, showed how nineteenth-century Dutch engineers were able to take advantage of new industrial technology. Now electric power is the main source of energy for lifting groundwater over the edge of a dike into one of the many drainage canals that carry it away. Added background information on Holland’s polder history was provided by Jandirk Hoekstra, of H+N+S Landscape Architects, during lunch on top of the Hondsbossche Zeewering, a huge barrier protecting the low-lying polder lands from the North Sea.

The Beemster and Schermer polders are reclaimed lakes. Elsewhere, polders consist of peat bogs that have been drained, dried, and flooded with silt supplied by the distributaries of the Rhine, Meuse, and Scheldt Rivers. Dairy farms and sheep grazing occupy these lands, since here the soil is not sufficiently rich to support crops. Like the converted lakes, these polders are maintained by continuous pumping to keep them from flooding, and next to every dike is a drainage canal.

A third kind of man-made land is that of the coastal plain, which accounts for much of the province of Zeeland. Maintaining the polder landscape here presents a much greater challenge. There have been historic floods in North Holland as well as Zeeland, one of the worst being that of 1953, when the North Sea flood killed two thousand people and inundated over 360,000 acres in this southwestern part of the country. Landscape architect Dr. Ingrid Duchhart (Wageningen University) and coast management specialists Jan Mulder (Deltares) and Leo Adriaanse (Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment) were our guides to the Delta Works. This vast coastal-engineering project consists of semipermeable storm-surge barriers with enormous bridges cum dams that connect Zeeland’s fringe of offshore islands. This impressive public works complex where the Scheldt and Meuse Rivers flow into the sea prevents inundation of the land in times of flood.

A third kind of man-made land is that of the coastal plain, which accounts for much of the province of Zeeland. Maintaining the polder landscape here presents a much greater challenge. There have been historic floods in North Holland as well as Zeeland, one of the worst being that of 1953, when the North Sea flood killed two thousand people and inundated over 360,000 acres in this southwestern part of the country. Landscape architect Dr. Ingrid Duchhart (Wageningen University) and coast management specialists Jan Mulder (Deltares) and Leo Adriaanse (Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment) were our guides to the Delta Works. This vast coastal-engineering project consists of semipermeable storm-surge barriers with enormous bridges cum dams that connect Zeeland’s fringe of offshore islands. This impressive public works complex where the Scheldt and Meuse Rivers flow into the sea prevents inundation of the land in times of flood.

Over lunch, Duchhart, Mulder, and Adriaanse said that “one hundred-year plans” to secure Holland from rising sea levels are being undertaken now. These incorporate both “hard” (dike constructions) and “soft” (sand supplement) solutions and include experimental approaches. When we noted the degree of uncertainty as to the success of various water-management strategies, we were reminded that from the outset the country’s existence has depended on informed experimentation with water, only now with more urgency that ever before.

Holland’s Golden Age and Beyond. A ramble through the recently reopened Rijksmuseum, with its beautifully renovated interior and restored paintings, and a tour of the Museum Van Loon, a historic town house on the Keizergracht canal (Amsterdam’s most prestigious address for wealthy burghers), provided a tangible reminder of the prosperity of the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, when the country enjoyed the fruits of a global commercial empire. We had a further taste of the period’s wealth and refinement during a canal trip on the Vecht led by Kees Beelaerts van Blokland. At the Vreedenhoff estate we admired the handsome eighteenth-century Rococo gate and beautifully maintained parterre garden; at the Gunterstein manor in Breukelen, the current owner showed us through a Romantic English-style landscape and working orchard; and at Castle Nijenrode, which is now owned by a university, the head gardener led us through the extensive grounds, which include gardens, a deer park, and picturesque vistas.

A walk through two estates in the Kennemerland, Beeckestein and Elswout, with landscape historians Lucia Albers and Michiel Veldkamp provided us with a further education in early Dutch landscape design. A Sunday afternoon stroll with landscape architect Korneel Aschman through Amsterdam’s Vondel Park – roughly contemporary with New York’s Central Park – showed how its Romantic landscape also serves as a modern playground for the city’s population, while at the same time offering pleasant views for those living in elegant town houses along its perimeter.

A walk through two estates in the Kennemerland, Beeckestein and Elswout, with landscape historians Lucia Albers and Michiel Veldkamp provided us with a further education in early Dutch landscape design. A Sunday afternoon stroll with landscape architect Korneel Aschman through Amsterdam’s Vondel Park – roughly contemporary with New York’s Central Park – showed how its Romantic landscape also serves as a modern playground for the city’s population, while at the same time offering pleasant views for those living in elegant town houses along its perimeter.

One persistent theme emerged as we continued our tour: the difficulty of preserving historic properties in an age of democratic socialism, when taxes are high and maintenance and operating costs formidable. At the seventeenth-century Amsterdam mansion Geelvinck Hinlopen, we were treated to a concert played on historic musical instruments, followed by a house tour and discussion with the owner-curators Jurn Buisman and Dunya Verwey about the way we in America are dealing with our own issues of heritage conservation. There was no shortage of ideas about how the Dutch could pick up on some of our recent efforts, but in the end most of us realized that our own country’s unique tradition of private philanthropy and tax laws encouraging charitable giving make it a difficult model to replicate in European nations, where government has in modern times played a strong role in supporting cultural patrimony.

This observation was borne out a few days later when we visited Castle Middachten in De Steeg. The castle’s owner, the Count zu Ortenburg, strives to meet his estate budget by charging groups such as ours for dinner in the castle’s grand dining room. Needless to say, many of us felt this to be the pinnacle of elegance on our itinerary, and we inevitably thought of the Henry Jamesian contrast between Old and New World cultures as we were welcomed by the count with perfect courtesy and perhaps the slightest hint of noblesse oblige. He made a point of the fact that we were dining on old family china, that the silver service had seen several generations, and that it was practically impossible to find a tablecloth today that was large enough to cover the length of the table where we sat.

This observation was borne out a few days later when we visited Castle Middachten in De Steeg. The castle’s owner, the Count zu Ortenburg, strives to meet his estate budget by charging groups such as ours for dinner in the castle’s grand dining room. Needless to say, many of us felt this to be the pinnacle of elegance on our itinerary, and we inevitably thought of the Henry Jamesian contrast between Old and New World cultures as we were welcomed by the count with perfect courtesy and perhaps the slightest hint of noblesse oblige. He made a point of the fact that we were dining on old family china, that the silver service had seen several generations, and that it was practically impossible to find a tablecloth today that was large enough to cover the length of the table where we sat.

Here too the issue of historic preservation came up, one made particularly difficult by the fact that the castle still belongs to the family of its original owners. With his mother’s recent death, the responsibility of ensuring Middachten’s survival has fallen on the Count zu Ortenburg’s shoulders, and he commutes frequently from his home in Frankfurt to take care of estate business. Hunting boar in his woods is still a passion (we were eating boar as a main course), as is riding. He admitted that he had little to do personally with the splendid garden that we had walked through before dinner, since he was too occupied overseeing other matters when in residence. One attempt to produce revenue involves opening the castle up to the paying public for Christmas festivities, when the house is lit with candles and resplendently decorated with green boughs. Another is hosting elegant dinners for paying guests such as ourselves. The historic-house preservationists among us proffered several other suggestions for increasing revenues, but for the most part our host dismissed these with studied politeness. One felt a pang of sympathy as we made our good-byes at the front door, when the count, making his gracious adieus, handed each of us a Middachten tourist brochure. It seemed clear to some of us that, whereas Henry James had foreseen the waning of the old life of aristocratic privilege in the age when impecunious noblemen married American heiresses, in our time we were witnesses to the last vestiges of a way of life that social democracies have made obsolete.

Since it is the property of the Dutch government, one historic landscape that does not have to ensure perpetuity through private means is Het Loo, the late seventeenth-century palace of William and Mary. Here, however, we encountered another issue regarding landscape restoration, this one philosophical in nature. As the Romantic movement swept Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many formal gardens were dismantled and their strict geometries and symmetry replaced with layouts in the English-garden style. This was the case with Het Loo. The question, therefore, is what to do in restoring such a historic garden when it has succumbed to age and neglect. Should it be regarded as a palimpsest of former designs and cultural tastes or returned to an archival plan and single historic period? In the case of Het Loo, the original, late seventeenth-century layout by Daniel Marot and Jacob Roman was chosen when the palace and garden were renovated between 1976 and 1982 and opened to the public as a state museum.

Since it is the property of the Dutch government, one historic landscape that does not have to ensure perpetuity through private means is Het Loo, the late seventeenth-century palace of William and Mary. Here, however, we encountered another issue regarding landscape restoration, this one philosophical in nature. As the Romantic movement swept Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many formal gardens were dismantled and their strict geometries and symmetry replaced with layouts in the English-garden style. This was the case with Het Loo. The question, therefore, is what to do in restoring such a historic garden when it has succumbed to age and neglect. Should it be regarded as a palimpsest of former designs and cultural tastes or returned to an archival plan and single historic period? In the case of Het Loo, the original, late seventeenth-century layout by Daniel Marot and Jacob Roman was chosen when the palace and garden were renovated between 1976 and 1982 and opened to the public as a state museum.

After viewing the central axis, parterres de broderie, and symmetrical plan from a window of an upper floor of the palace, we were given a tour by the current head gardener, Willem Zieleman, who explained that another reconstruction campaign was under way. We could see several men operating heavy equipment. It turned out that they were renovating the infrastructure and replacing the soil and gravel paths in the Queens Garden. As we moved down the great central allée toward the colonnade at the end of the parterre, we were informed that this was not the terminus of the William and Mary garden, as it was formerly thought to be. Beyond the colonnade workers have discovered, buried beneath the grass of the eighteenth- century Romantic garden, the former axial extension that carried the eye beyond the colonnade to the wooded horizon. With fidelity to the 1685 plan, the plants in the beds between the arabesques of the box hedges of the parterre are now carefully selected period specimens. Among these are some of the variegated striped tulips that were once objects of the collectors’ craze known as “tulipomania.”

After viewing the central axis, parterres de broderie, and symmetrical plan from a window of an upper floor of the palace, we were given a tour by the current head gardener, Willem Zieleman, who explained that another reconstruction campaign was under way. We could see several men operating heavy equipment. It turned out that they were renovating the infrastructure and replacing the soil and gravel paths in the Queens Garden. As we moved down the great central allée toward the colonnade at the end of the parterre, we were informed that this was not the terminus of the William and Mary garden, as it was formerly thought to be. Beyond the colonnade workers have discovered, buried beneath the grass of the eighteenth- century Romantic garden, the former axial extension that carried the eye beyond the colonnade to the wooded horizon. With fidelity to the 1685 plan, the plants in the beds between the arabesques of the box hedges of the parterre are now carefully selected period specimens. Among these are some of the variegated striped tulips that were once objects of the collectors’ craze known as “tulipomania.”

Of course, one cannot think of the Netherlands without thinking of tulips, but their importation and cultivation in Holland is but one facet of the country’s long botanical history and floriculture. The town of Leiden boasts a famous university, to which is attached the Hortus Botanicus, Europe’s third-oldest botanical garden, dating back to 1590. Here we walked around with Carla Teune, starting our tour in the enclosed Clusius Garden, recently restored according to seventeenth-century engravings. This garden is named for the famous botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), who as the first prefect of the university established the Hortus as an important plant distribution center and collection of materia medica for students. Such recently discovered American plants as tobacco and potatoes were naturalized here and then brought into cultivation in Europe. Clusius’s name is also associated with the tulip, and it was in this botanical garden that the signature plant of Holland was first displayed after being imported from Turkey. Strolling the larger grounds outside the Clusius garden, we beheld some of the majestic trees contributed by eighteenth-century botanists such as Herman Boerhaave and Philipp Franz von Siebold. These and other specimen trees, shrubs, and perennials bear binomial Latin labels, witness to the taxonomic system of Carolus Linnaeus, who furthered his plant-identification nomenclature here during his 1735–38 sojourn in Leiden and Amsterdam. The traditional Linnaean order of the plant-family beds along the eastern border of the garden was rearranged recently to reflect the latest advances in molecular plant science.

Of course, one cannot think of the Netherlands without thinking of tulips, but their importation and cultivation in Holland is but one facet of the country’s long botanical history and floriculture. The town of Leiden boasts a famous university, to which is attached the Hortus Botanicus, Europe’s third-oldest botanical garden, dating back to 1590. Here we walked around with Carla Teune, starting our tour in the enclosed Clusius Garden, recently restored according to seventeenth-century engravings. This garden is named for the famous botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), who as the first prefect of the university established the Hortus as an important plant distribution center and collection of materia medica for students. Such recently discovered American plants as tobacco and potatoes were naturalized here and then brought into cultivation in Europe. Clusius’s name is also associated with the tulip, and it was in this botanical garden that the signature plant of Holland was first displayed after being imported from Turkey. Strolling the larger grounds outside the Clusius garden, we beheld some of the majestic trees contributed by eighteenth-century botanists such as Herman Boerhaave and Philipp Franz von Siebold. These and other specimen trees, shrubs, and perennials bear binomial Latin labels, witness to the taxonomic system of Carolus Linnaeus, who furthered his plant-identification nomenclature here during his 1735–38 sojourn in Leiden and Amsterdam. The traditional Linnaean order of the plant-family beds along the eastern border of the garden was rearranged recently to reflect the latest advances in molecular plant science.

Modernist and Present-day Landscape Design. A stop at the Kröller-Müller Museum, which sits within the National Park Hoge Veluwe, opened our eyes to another aspect of the Netherlands: its wooded eastern landscape, with hills and heatherfields. A fascinating underground visitor center provided a fine introduction to the area’s geological underpinnings and wildlife. While some members of our group rented bicycles and took off on one of the trails through the woods, others walked through the seventy-five-acre sculpture garden surrounding the museum, which is renowned for its collection of works by Vincent van Gogh. The museum and garden embody the vision of art collector Helene Kröller-Müller, who sought to create an environment in which painting, sculpture, architecture, and nature are seen in symbiotic harmony, and ideal that is furthered by architect Wim Quist's 1977 wing.

The Netherlands and Belgium are today at the forefront of the profession of landscape design, thanks to a creative modernist tradition that has been built upon by contemporary practitioners, most notably Piet Oudolf and Peter Wirtz. Our group was fortunate to be able to meet with both artists on visits to the respective gardens in which they work experimentally and have their firms’ offices.

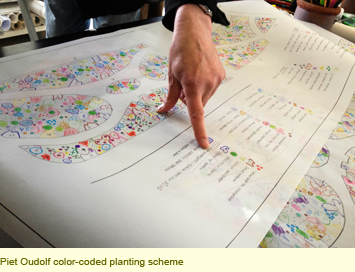

Oohs and ahs punctuated each turn in Oudolf’s garden, where imaginatively clipped hedges provided the confining architecture for flowing tapestries of seemingly uncultivated vegetation. Later we talked with Piet and his wife Anya in a big, light-filled studio. There he works out color-coded planting schemes for clients in drawings that can evoke Gertrude Jekyll’s garden plans, reenvisioned in a contemporary mode – “Jekyll on steroids,” as someone remarked. As did Jekyll, Oudolf has a wealth of horticultural knowledge to draw upon when imagining color harmonies, textural contrasts, and flowing combinations of plants that capitalize on seasonal change in artful ways.

Oohs and ahs punctuated each turn in Oudolf’s garden, where imaginatively clipped hedges provided the confining architecture for flowing tapestries of seemingly uncultivated vegetation. Later we talked with Piet and his wife Anya in a big, light-filled studio. There he works out color-coded planting schemes for clients in drawings that can evoke Gertrude Jekyll’s garden plans, reenvisioned in a contemporary mode – “Jekyll on steroids,” as someone remarked. As did Jekyll, Oudolf has a wealth of horticultural knowledge to draw upon when imagining color harmonies, textural contrasts, and flowing combinations of plants that capitalize on seasonal change in artful ways.

If Oudolf is a contemporary master of the painterly garden, Jacquez Wirtz and his son Peter can be said to be the masters of the sculptural landscape. This is a simplification, of course, because Oudolf uses hedges to great effect, and the Wirtzes, father and son, are also great plantsmen. The morning we spent with Peter brought home the fact that the greatest landscape designers are first and foremost gardeners. “Soil!” exclaimed Peter at one point. “The soil here is so sweet and rich I could eat it!” Clearly, it is this passion for the earth itself that animates his work, as he continues on an international scale the practice begun by his father Jacques. This passion is also reflected in his great concern for plants and trees – the beech, for example – threatened with demise in the next decades due to global warming. A trip to the Belgian town of Mol-Rauw took us beyond the cloud-clipped hedges of the family garden in Schoten into a Wirtz-designed landscape on a much larger scale. Here the owners of an old sand-mining business had asked the firm to convert an abandoned quarry into a semipublic park. Wandering about in the rain, we admired the great swaths of tall Miscanthus hybrids and other grasses, as well as natural woodlands surrounding sky-reflecting water bodies on this once-industrial site.

If Oudolf is a contemporary master of the painterly garden, Jacquez Wirtz and his son Peter can be said to be the masters of the sculptural landscape. This is a simplification, of course, because Oudolf uses hedges to great effect, and the Wirtzes, father and son, are also great plantsmen. The morning we spent with Peter brought home the fact that the greatest landscape designers are first and foremost gardeners. “Soil!” exclaimed Peter at one point. “The soil here is so sweet and rich I could eat it!” Clearly, it is this passion for the earth itself that animates his work, as he continues on an international scale the practice begun by his father Jacques. This passion is also reflected in his great concern for plants and trees – the beech, for example – threatened with demise in the next decades due to global warming. A trip to the Belgian town of Mol-Rauw took us beyond the cloud-clipped hedges of the family garden in Schoten into a Wirtz-designed landscape on a much larger scale. Here the owners of an old sand-mining business had asked the firm to convert an abandoned quarry into a semipublic park. Wandering about in the rain, we admired the great swaths of tall Miscanthus hybrids and other grasses, as well as natural woodlands surrounding sky-reflecting water bodies on this once-industrial site.

Looking back on our trip, we remembered an even more intimate contact with Dutch soil on the evening that we dined at De Kas situated in Frankendael Park, which occupies farmland outside Amsterdam. Before sitting down to eat in the airy, eight-meter-tall greenhouse that serves as the restaurant cum nursery, we perched on stools beside high tables and munched on delicious seasoned carrots and gargantuan, flavorful olives that had been set out in little bowls. Nearby were flats in which multiple varieties of tomato seedlings – the kind that are now go under the umbrella name “heirloom” – were growing. Our host, local-food apostle, Michelin-star chef, and owner Gert Jan Hageman, gave us a history of his unusual enterprise: “Before this I was a chef and had created three successive restaurants,” he said. “But my wife, who is also my business advisor, learned about this farm with these abandoned greenhouses that had previously been the Amsterdam Municipal Nursery. She knew I was tired of cooking haute cuisine, and she convinced me to buy the property. It seemed a crazy thing to do at the time, but I decided I wanted to create dishes from ingredients we grow right here and make dishes that are both delicious and healthy. So we restored the greenhouses and began propagating vegetables and cultivating the surrounding fields. Now I’m a farmer and spend most of my time planting and digging, and my staff does the cooking. We have the most fantastically rich soil,” he concluded. Looking at his roughened hands and the dirt beneath his fingernails, we realized that here was a farmer indeed. It was good to know the man who had grown, planned, and overseen the preparation of what turned out to be an incomparable meal.

Clearly this tour, organized by landscape historian Vanessa Sellers on behalf of the Foundation for Landscape Studies, provided an on-the-ground (in-the-rain) educational experience of Dutch and Belgian gardens at the highest level. Because, like the other occasional tours the foundation sponsors, this trip was grounded in landscape history, Sellers provided the participants with a bibliography; a landscape-history synopsis titled “Four Centuries of Gardening in the Netherlands: 1600-2000,” based on an overview originally drawn up by Dutch garden historian Carla Oldenburger-Ebbers; a list of important Dutch garden designers; and a list of links to Dutch water-management websites provided by H.E. Mr. Herman Schaper, Dutch Ambassador to the United Nations and one of the primary participants in ongoing discussions during the Year of International Water Cooperation.

We hope that these “hand-outs,” along with the photographs we have assembled, will provide our Foundation for Landscape Studies website visitors with suggestions and ideas for itineraries of their own.To view an online slideshow of photographs from this tour, please click here.