Place Travels

- The Healing Angel of Central Park

- A Rush to Drill, Because We Can

- Discover garden paradises, granite boulders, and moss-carpeted forests.

- New York Environs

- Romantic Rome

- Villa Lante

- Vaux-le-Vicomte

- Two Cities, Two Parks: Saturday in Paris, Sunday in New York

- Traveling Through the Netherlands and Belgium

Two Cities, Two Parks: Saturday in Paris, Sunday in New York

Paris, Saturday, August 24, 2013. The best remedy I know for jet lag is a long walk. Needless to say, Paris is nonpareil for this kind of fresh-air cure.

Today, after checking into our Left Bank hotel, we crossed the Pont Royale and found ourselves in the Tuileries, where we were amazed to see a giant Ferris wheel next to the Rue de Rivoli. No, it was not a clone of the London Eye, but—thank goodness—only a ride that was part of the temporary, summer midway running along the north edge of the gardens. Come to think of it, the big wheel with its LED-embellished spokes was a rather stunning addition to the Parisian skyscape.

Today, after checking into our Left Bank hotel, we crossed the Pont Royale and found ourselves in the Tuileries, where we were amazed to see a giant Ferris wheel next to the Rue de Rivoli. No, it was not a clone of the London Eye, but—thank goodness—only a ride that was part of the temporary, summer midway running along the north edge of the gardens. Come to think of it, the big wheel with its LED-embellished spokes was a rather stunning addition to the Parisian skyscape.

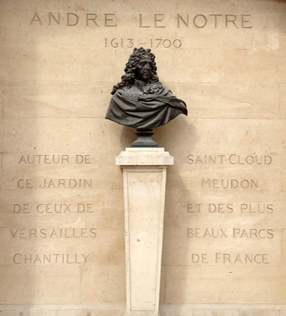

The gardens themselves were anything but carnivalesque. We strolled to the end where a bust of André Le Nôtre ornaments a niche in the tall horseshoe-shaped wall embracing the great circular basin that is one of his signature elements as a landscape designer. Ascending one of a pair of grand staircases to the terrace in front of the Place de la Concorde, we gazed up the Champs Elysées to the Arc de Triomphe. Turning around, we had a wonderful perspective of the Tuileries in all its symmetrical, axial entirety.

The gardens themselves were anything but carnivalesque. We strolled to the end where a bust of André Le Nôtre ornaments a niche in the tall horseshoe-shaped wall embracing the great circular basin that is one of his signature elements as a landscape designer. Ascending one of a pair of grand staircases to the terrace in front of the Place de la Concorde, we gazed up the Champs Elysées to the Arc de Triomphe. Turning around, we had a wonderful perspective of the Tuileries in all its symmetrical, axial entirety.

Before going back down to the gardens, we stood awhile watching a busker who was coated head to toe with bronze paint. He immobilized himself like a statue and then coyly mimed an invitation in slow motion to someone in the knot of people gathered nearby, inviting her to come and shake his hand.

This year marks the four-hundredth anniversary of the birth of André Le Nôtre, a good reason – if any were needed—to realign the contemporary appearance of the Tuileries with that of the still-unrivaled French landscape designer’s reordering of Catherine de Medici’s palace gardens during the reign of Louis XIV. A restoration designed more than ten years ago by competition winners Pascal Cribier and Louis Benech is still in progress, and we noted how the clarification, replanting, and sculptural adornment of Le Nôtre’s overgrown bosquets had proceeded since our last visit.

But mostly it was that agreeable placidity conferred by Paris’s humane tempo and the ineffable, soft, bluish light that turned the day into one of pure delight. As we strolled back toward to the site of the former Tuileries Palace at the opposite end of the garden, we passed couples quietly conversing or reading on benches beneath the allées of trees on either side of the central promenade and noted the profusion of late summer flowers bordering immaculately mown green turf, where fancy parterres de broderie once commanded the attention of an army of gardeners.

But mostly it was that agreeable placidity conferred by Paris’s humane tempo and the ineffable, soft, bluish light that turned the day into one of pure delight. As we strolled back toward to the site of the former Tuileries Palace at the opposite end of the garden, we passed couples quietly conversing or reading on benches beneath the allées of trees on either side of the central promenade and noted the profusion of late summer flowers bordering immaculately mown green turf, where fancy parterres de broderie once commanded the attention of an army of gardeners.

When we arrived at the Grand Carré, the open area with its large, circular, sky-reflecting, Le Nôtre basin with its fountain jet punctuating the eastern end of the grand central axis, we sat in a pair of the attractive, backward-leaning, contemporary, green, metal chairs that have been placed around it. Then for the next half hour we rested, gazing up at Napoleon’s triumphal arch, the Louvre, and the luminous sky as we watched other people in the same state of happy relaxation. Indeed, there was no more jet-lag fatigue, for here we were in the heart of irresistible Paris in a moment of late-afternoon perfection.

When we arrived at the Grand Carré, the open area with its large, circular, sky-reflecting, Le Nôtre basin with its fountain jet punctuating the eastern end of the grand central axis, we sat in a pair of the attractive, backward-leaning, contemporary, green, metal chairs that have been placed around it. Then for the next half hour we rested, gazing up at Napoleon’s triumphal arch, the Louvre, and the luminous sky as we watched other people in the same state of happy relaxation. Indeed, there was no more jet-lag fatigue, for here we were in the heart of irresistible Paris in a moment of late-afternoon perfection.

New York, Sunday, September 1, 2013. Seeking the same remedy for jet lag that succeeded last week, I took a long walk in Central Park this morning. Now I was no longer in the world of Le Nôtre, but rather in the urban Arcadia devised by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.

Besides the disparity in size—843 versus 63 acres—there are obvious historical and cultural differences between the New York park and the Tuileries. Instead of a garden in the French, seventeenth-century, classical style, Central Park is a nineteenth-century Romantic landscape; and whereas the Tuileries was long the preserve of royalty and the aristocracy, Central Park was built as a people’s park, a signal expression of American democracy.

There is another important difference besides those just mentioned. As I passed through Strawberry Fields and took the path north of Sheep Meadow to the Mall, I remembered how tranquil and comparatively decorous the Tuileries had seemed the week before, especially when I noticed all the physical activities going on around me now. It was true that Central Park was also pervaded by an air of calm, but here recreation rather than relaxation was the dominant mode. There were runners and cyclists in a fast-moving stream on the curving drives rather than slow promenaders strolling along the wide straight central allée lined with sheer walls of clipped plane trees, so unlike the Mall— Central Park’s single formal axis—where the pendulous branches of double rows of American elms form a loose overarching canopy. Here I noted another difference: the axis of the Mall ends not in architectural grandeur as did that of the Tuileries before the Palace was destroyed in 1871 by the Communards but instead simply melts into the scenery of the Lake and Ramble beyond. Furthermore, while both promenades have circular fountains at their terminuses, that of the Mall is not revealed until you descend a broad staircase and move through the passageway of the Terrace Arcade. Only then do you behold, instead of an exclamatory jet of water, the two-tiered fountain with downward arcing streams spilling into the large round pool in which lotuses float. Here, rather than a statement of monarchial power, is a symbol of civic beneficence, the crowning sculpture of the Angel of Bethesda commemorating the abundant supply of pure water made possible by the opening of the Croton Aqueduct in 1842.

There is another important difference besides those just mentioned. As I passed through Strawberry Fields and took the path north of Sheep Meadow to the Mall, I remembered how tranquil and comparatively decorous the Tuileries had seemed the week before, especially when I noticed all the physical activities going on around me now. It was true that Central Park was also pervaded by an air of calm, but here recreation rather than relaxation was the dominant mode. There were runners and cyclists in a fast-moving stream on the curving drives rather than slow promenaders strolling along the wide straight central allée lined with sheer walls of clipped plane trees, so unlike the Mall— Central Park’s single formal axis—where the pendulous branches of double rows of American elms form a loose overarching canopy. Here I noted another difference: the axis of the Mall ends not in architectural grandeur as did that of the Tuileries before the Palace was destroyed in 1871 by the Communards but instead simply melts into the scenery of the Lake and Ramble beyond. Furthermore, while both promenades have circular fountains at their terminuses, that of the Mall is not revealed until you descend a broad staircase and move through the passageway of the Terrace Arcade. Only then do you behold, instead of an exclamatory jet of water, the two-tiered fountain with downward arcing streams spilling into the large round pool in which lotuses float. Here, rather than a statement of monarchial power, is a symbol of civic beneficence, the crowning sculpture of the Angel of Bethesda commemorating the abundant supply of pure water made possible by the opening of the Croton Aqueduct in 1842.

There were numerous people rowing on the Lake. In the bosky Ramble with its irregular paths winding this way and that, I spotted a group of bird-watchers who could have been on a field trip in the Adirondacks. What a far cry is this simulated natural woodland cum wildlife preserve from the geometrically ordered square bosquets of the Tuileries with their borders of pollarded trees and sculptures rather than squirrels! You could generalize and say that the Tuileries is about interpersonal sociability and passive reflection whereas Central Park, although also a quiet oasis, is an open-air theater of spectacle and activity, its users being both actors and audience. Both parks are wonderful, each according to its own ethos.

There were numerous people rowing on the Lake. In the bosky Ramble with its irregular paths winding this way and that, I spotted a group of bird-watchers who could have been on a field trip in the Adirondacks. What a far cry is this simulated natural woodland cum wildlife preserve from the geometrically ordered square bosquets of the Tuileries with their borders of pollarded trees and sculptures rather than squirrels! You could generalize and say that the Tuileries is about interpersonal sociability and passive reflection whereas Central Park, although also a quiet oasis, is an open-air theater of spectacle and activity, its users being both actors and audience. Both parks are wonderful, each according to its own ethos.

Remember how scary the Ramble used to be and how uncivilized Central Park had become back in the 1970s and early ’80s? At that time the French parks seemed to be comparative paradises of cleanliness, order, and civility. If only we could get rid of the drug dealing and the fifty thousand square feet of graffiti on stonework, walls, and monuments in Central Park! If only we could turn bare meadows and lawns of compacted soil into grassy turf . . . If only we could reinstate the kind of horticultural care and grounds maintenance we had once and Parisian parks still enjoyed . . .

It has become anecdotal in the retelling, but I still remember the day in 1979, shortly after I had been appointed the park’s administrator by Mayor Ed Koch, when French architect Antoine Grumbach appeared in my office. He was positively brimming with enthusiastic appreciation for Central Park, even in its all-too-apparent state of degradation. What a lively place he thought it, in comparison to the parks of Paris. “You see,” he exclaimed, “it is terrible how we have all these gardeners and all they care about is keeping everything tidy and manicured! Here you have people—people doing whatever they want and nobody telling them to keep off the grass!” I didn’t point out that there was hardly any grass left in the park, only weeds. Then I began to think of how we might strike a deal. Hmmm . . . sixty graffitists for six gardeners? Happily, Central Park’s fortunes were reversed, and under the management of the Central Park Conservancy, it has undergone a thorough and ongoing restoration and is today as impeccably maintained as the Tuileries.

It has become anecdotal in the retelling, but I still remember the day in 1979, shortly after I had been appointed the park’s administrator by Mayor Ed Koch, when French architect Antoine Grumbach appeared in my office. He was positively brimming with enthusiastic appreciation for Central Park, even in its all-too-apparent state of degradation. What a lively place he thought it, in comparison to the parks of Paris. “You see,” he exclaimed, “it is terrible how we have all these gardeners and all they care about is keeping everything tidy and manicured! Here you have people—people doing whatever they want and nobody telling them to keep off the grass!” I didn’t point out that there was hardly any grass left in the park, only weeds. Then I began to think of how we might strike a deal. Hmmm . . . sixty graffitists for six gardeners? Happily, Central Park’s fortunes were reversed, and under the management of the Central Park Conservancy, it has undergone a thorough and ongoing restoration and is today as impeccably maintained as the Tuileries.

Well, here I have confirmed that the best prescription for overcoming jet lag is walking around in pubic places. For me, all in a single week, this was the Tuileries and Central Park. Both are the green centers around which their respective urban environments coalesce, completely unlike one another in style and atmosphere, yet therapeutic each in its own way. Two world-class cities, two amazingly beautiful and popular parks: There is nothing left to say on this score except vive la différence!